|

Oracle is a pretty good little walking town. Lots of folks are up and about early these days to beat the heat and enjoy the landscape. Some are quite disciplined - daily, twice daily, couples, groups, even step counters racking up big numbers. For myself it's beauty of place, the company, the encounters with friends and (sometimes new) neighbors that makes the walkabouts so gratifying. When you think about it, it's a whole lot safer to meet strangers on the road than walking up a driveway and banging on the front door. In that case you might be greeted by a cold stare leveled behind cold steel. That happened in our neighborhood to a woman who thought she was approaching the right house hosting a baby shower. Wrong. The experience left her shaken, even traumatised. Speaking of being traumatised, how would you react to encountering someone who looks like this? I freaked out until Kaz assured me it was just our next door neighbor walking while netted.

0 Comments

To outsiders - some politicians, distant bureaucrats, and residents of neighboring planned communities - it may appear insignificant. What's the fuss about cutting the county's free trash voucher program in half (from 6 to 3) and raising some bureaucratic hoops in the process? No big deal, right?

But stop to consider this: In the real world of Oracle and its environs, the free voucher program at minimal cost has reduced desert dumping, cut into backyard trash accumulation, cut fire risk and encouraged neighborliness of mutual aid. Not to mention helping out with family budgets. So maybe what looks like "little stuff" to outsiders matters a lot to the folks who live in Oracle and the other communities in the Copper Corridor. -------------- There's another angle on this situation that bears consideration. That is how local government can turn local relationships into an excercise in suspicion. Distancing the voucher program (and obviously so many others) means applicants are by definition suspect. Who are you really and are you worthy of what what we're conditionally bestowing on you if you manage the hoops properly. If you don't you're just plain stupid or technologically incompetent which is another way of saying the same thing. Small communities in the Copper Corridor are still face-to-face and trust based. We give up that ground grudgingly. Our Florence Goverment is severing those ties bit by bit. Game the system for a voucher? OMG. Scottsdale lawyers fronting Goliath developers know what gaming the system really means. They're talking millions and tens of millions not nickels and dimes. The Blue Collar/White Collar Divide And What The Oracle Community Center Has To Do With It7/17/2022 The Oracle we moved into in 1979 was a blue collar town. Sure there was a handful of mining executives building on hill tops but everyone else was employed in mine work, ranch work or hard scrabble small business. Even the revolutionary changes wrought by the Rancho Linda Vista art colony were hands on (blue collar) in nature. (A visit to the workshops of RLV made that abundantly clear. Dirty hands, weird weldings, strange fabrications on desert paths and the like were the order of the day.) At that time Oracle residents lionized "blue collar" excellence - endurance and skills underground and/or in mill or smelter; cement work, block laying, framing, sheetrocking, roofing; heavy equipment operations. I rarely heard of someone praising IT skills, lawyering, marketing, accounting or executive management and the like. In the economy of local respect, wealth didn't figure. No one was that rich anyway and the few that had some extra bucks gained no particular esteem for it. One important venture in the 1980's illustrates my point, namely, construction of the Oracle Community Center. A cracked slab was all that had been accomplished by a group formed up originally to build it. The slab lay fallow along with the dollars raised to complete the building. In the early 1980's there were board conflicts (which is a story for another time) but the bottom line is locals turned out to put the building up with whatever skills they brought to the project or were willing to learn on the job. Pivotal in this effort was Central Arizona College/Aravaipa Campus building trades instructor Glen Johnson. Glen took the Community Center project on with several of his classes, pitched in himself, and mentored the rest of us. Kaz and I loved the guy for who he was and what he accomplished. We also noted the number of fellow residents who swung into action workday after workday. With volunteer labor the building ended up costing $15 a square foot (total 2800 square feet), a remarkable and enduring achievement. When Kaz and I moved to Oracle we were mightily impressed by the number of residents who could make things - sometimes beautiful, sometimes functional, sometimes a combination of the two. We called on some of them to improve the old house we had just purchased. Not just Dub Ragels, the plumber, but others who had learned their trades as carpenters, boilermakers, welders, heavy equipment operators and the like. Of course, at first we had no idea what mine, mill and smelter work had to do with proliferation of "the crafts" in Oracle. But listening to the connections embedded in personal stories helped assemble a picture of how mining informed so many work lives. On the farm where my grandfather grew up, a place where generations of Pierson owners labored mightily on the same acreage as far back as 1790, mastery of the skills, habits and practices that small scale farming entails meant the difference between living decently and forfeiture of the land itself. In current times Orrin and Jackie Pierson raised four remarkable daughters there one of whom is named after my mother. The story continues. Frank and Rita, my parents, actually made jokes about my father being unable to hammer a nail into a wall to hang a picture. So different was my upbringing from the demands and satisfactions of farm life. Silas Pierson's boys - four including my father - were raised in Denver in a family headed by a major corporate executive with the resources to pay others to perform what was then described as "manual labor". Silas himself was raised on the Pierson Farm but thereafter kept his distance - except to visit, lend money and offer pointed management advice from time to time.

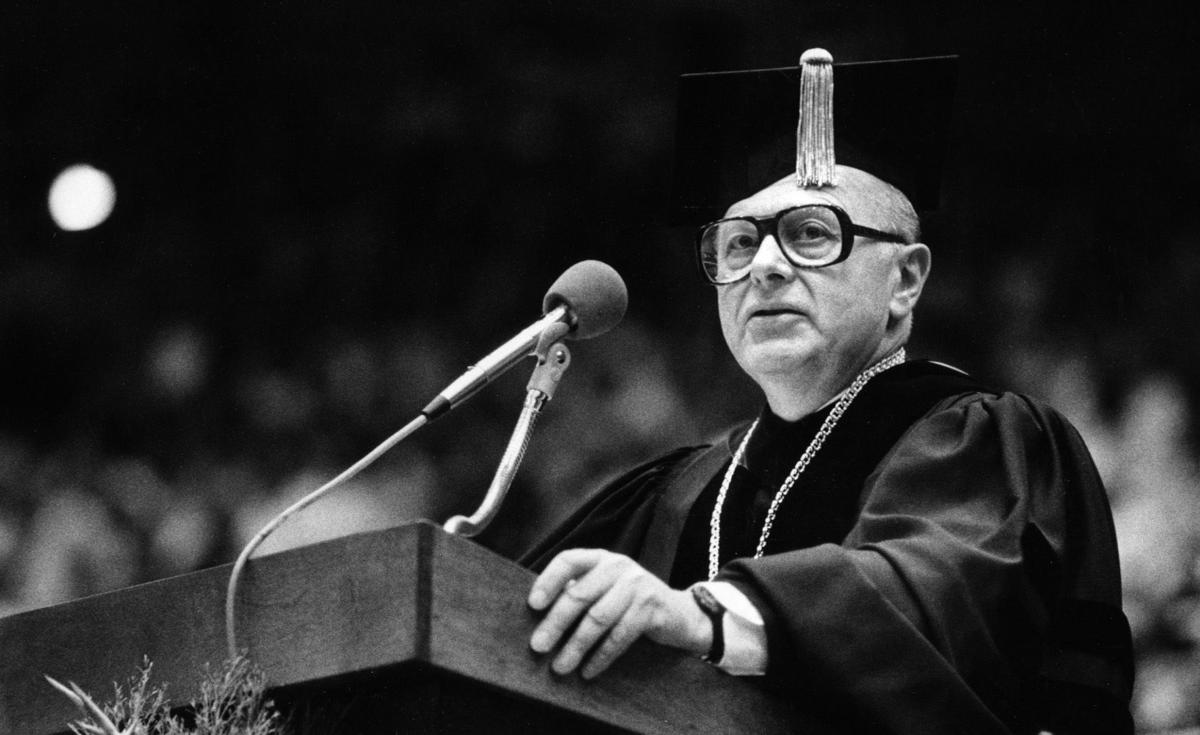

------------------- The individual in family history with whom I most identify in our move to Oracle is my uncle Orrin. Though he died before I was born (as did two of his siblings) the arc of his life in some ways resembled and even inspires mine. Orrin was at first a reluctant farmer - driven by necessity to take over the Pierson Farm with his wife Edna during the Great Depression. Thereafter they plunged into farm and community life. Orrin turned his farming experience into grist for his other passion - writing. He proved a very good writer, authoring some 1,000 columns for the local newspaper thereby becoming a revered player in community life in the process. Many of those columns authored by Orrin as The Gleaner, were published posthumously in a wonderful little book, Off Our Back Stoep, The Chronicle Of A Farmer's Year. I acknowledge that drawing parallels between farming, the trades and organizing is a stretch but perhaps not quite as far as it appears on first glance. At root community organizing is a trade focused on habits and practices of local relationship building and concrete action - not the more grandiose schemes of "revolutionary" social change that attract some of its practitioners, including myself, from time to time. University officials along with President Henry Koffler were caught red handed by explosions and a fire at the toxic waste dump of its own making. In Oracle a leadership group formed up.

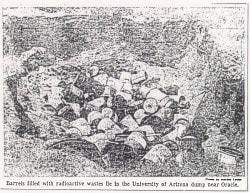

Oracle citizens demanded that the University stop dumping their toxic waste in Pinal County, dig up what had already been deposited, monitor for any residuals that might be moving towards the aquifer, and monitor the groundwater itself with deep wells. The University of Arizona stonewalled. Simple questions went answered. A number of University professors were walked out to declare the dump posed no threat to regional groundwater. Oracle citizens launched a campaign to both elevate the issue in the public eye and challenge political leaders to make the demanded changes. In January, 1983 the conflict hit the Tucson papers as well as The San Manuel Miner. Kaz and I were among the local spokespersons, attacking the University’s practices, its failure to answer questions and attempts to cover up disturbing findings as they emerged. Kaz and I were eating breakfast at Mother Cody’s Cafe in the early 1980's when local attorney Jeffrey Blackman approached our table.

“The University of Arizona is poisoning our water,” he said to us and anyone else within earshot of his loud proclamation. “They’re running a hazardous waste dump on top of our water supply,” he shouted even louder. “Oracle will be poisoned by a toxic brew moving down stream from the ranch where it was deposited. Maybe it already is.” Blackman produced an Arizona Daily Star report that detailed Pinal County official’s shock at learning of University waste disposal practices. A fire at the dump site, mistaken for a downed aircraft from Davis Monthan Air Base, blew the whistle. Dumping of chemical and radioactive waste into open trenches across county lines had been ongoing for decades. The trenches were water traps in monsoon times, driving pollutants towards Oracle’s aquifer. Pinal County officials accused the University of “sneaking into Pinal County” to deposit its waste. The offending dump was located on ranch property a few miles from Oracle that had been owned and operated by J T Page. Page made the purchase later in life when migrating west. He intended to manage ranch land in a way that relied on rainwater and resisted mechanized farming with chemical fertilizers and weed killers. At his death in 1940 he gave the land to the University of Arizona conditioned on furthering his passion for arid lands research. We obviously didn’t know shit from shinola about water or household waste and for good reason. Both of us had lived in cities and suburbs where such matters were invisible to us. In fact, climbing mostly up hill 30 miles out of Tucson for our first visit suggested by a real estate agent, Oracle seemed to us a sparsely populated near wilderness where we breathed easier. Light traffic, oak, juniper, manzanita along with cholla and prickly pear cactus. Cooler. No tract homes. No stoplights. A handful of small businesses strung out on a street called American Avenue. Lots of open space. The Santa Catalina mountains as a backdrop.

The entrance to town back then was marked by an aging trailer park. 44 years later it still raises the hackles of some newcomers looking for the town to go a bit more upscale. But for us, like the price of water, it seemed a small price to pay for disincentivizing growth - not to mention a place for some folks to live on a shoestring. After the trailers we noted an auto repair shop, a quaint cafe called Mother Cody’s, an Exxon gas station. Across the road was a compact structure with a sign that read Oracle Inn, Bar and Restaurant. We turned right, two blocks up an unnamed street to a small park then to a driveway just beyond. Winding, rutted. Strung out on a gentle ridge, invisible from the road, was a house with an odd second story on one end. To the left a cavernous doorless garage. We couldn’t contain ourselves, A bit ramshackle with lots of privacy. Inside, the green shag rug in the living room, tiny kitchen, and multiple cracked window frames failed to diminish our enthusiasm. The house was big enough for all the kids we hoped to raise there. "Serendipity,” our agent declared. Maybe so but she didn’t think to require testing of the septic system much less inquiry into the leaky faucets - and neither did we. Fred and Eunice, the owners, refused a face to face meeting on moral grounds. Eunice declared to our agent that we were “an immoral couple” because we weren’t married. She opined that our relationship would never last. (She passed away long before she could test her hypothesis.) Nonetheless, suspending their principles, they took our money. We never did meet either of them, even at the closing, but we got the deed to the property. On move in day census figures put the population of Oracle at about 2,800. All the faucets leaked and two toilets didn’t flush properly in the house Kaz and I bought in 1979. Our first order of business was to find a plumber. Turns out there was one in Oracle whose name was Delbert “Dub” Ragels. When Dub showed up after greetings and a few other niceties he fixed the worst offending leaky faucets, then suggested that we’d better learn to change the washers ourselves or we’d soon run out of money. “This is Oracle,” he said. “But don’t get me wrong, I like the business.” As he was about to return to his truck, I stopped him.

“We have another problem,” I said, “that maybe you can help us with. The toilets don’t seem to flush right. He turned with a half smile on his face said something like “maybe the septic tanks are full”. Then he pulled the covers off both tanks exposing two god awful stinky messes that featured plastic cleaning pads amid the rancid fecal stew. “At a minimum they need to be pumped.”. “Who does that?” “I do,” “But the real problem may be the leach lines.” “What’s that?” “That’s where the tank drains into the soil. A lot of times roots block the flow of liquids. Back in the day they used clay tiles laid end to end. Easy for the roots to get in. I don’t know for sure that’s the problem. Haven’t worked on the place. Fred and Eunice never hired local. Didn’t want anyone around here to know their business.” Depressed by the situation we at least felt a bit righteous because unlike the previous owners we thought local hires were the way to go. The day after Dub left the premises I began digging up the leach line from the main septic tank. It was pick and shovel work. After an hour or so a clunk announced my pick’s encounter with what proved to be one of the clay tiles Dub predicted. I cleaned out the trench. Sure enough there were roots penetrating the tiles one after another at every joint. Those I pulled out were completely plugged. New plastic drain pipe leading to one end of the exposed rocky leach field solved the problem. After that, and for over a decade, our toilets flushed properly. It seemed a hard won triumph until at a New Years Eve party our main toilet backed up and water began flooding into the living room under the bathroom wall. Pride goeth before a fall. Our neighborhood, he (Bill Collier) wanted us to know, was Oracle’s first platted and zoned subdivision - Oracle State Tracts. Our house, he said, was built in part by Henry and Nell Nichols adding to a preexisting structure erected by a hard scrabble miner using 6 inch concrete block.

The holes in all the screen frames he explained were cut outs that enabled a firearm - shotgun, hand gun, rifle - wielded by Nell Nichols to pass through and blast away at predators endangering her beloved quail. She was, he said, a good shot. The large, sloping, cracked slab next door was constructed as an attempt to trap water before the Arizona Water Company arrived in town. Trap water it did which promptly drained through a fracture in the hand dug well and replenished a neighbors windmill driven hand dug well next door. Mr. Collier went on to introduce us to Mother Magma - Magma Copper Company, ten miles distant - which had employed him before his retirement. “They pretty much run everything around here.” He explained that Pinal County boss Jay Bateman retaliated against his opposition typical of the political boss he was. Collier’s own resistance to one Bateman initiative was met by county public works slashing a road through his property and cutting down one of his huge, prized oaks in the process. How We Got Here

Meetings and one-on-one conversations in Oracle often begin with “how did you get here" stories. They’re diverse with many following family lineage back into mine work. Silver City, Superior, Sonora, Mammoth, Christmas, Jerome. Underground, heavy equipment, smelter, railroad, stamp mill. No so ours. There’s mining (and farming) in my family history but my wife Kaz and I bought property in Oracle in March of 1979 almost by chance. Kaz grew up part time in Tucson and wanted to move back to the desert. Movig here from Queens, NYC became a serendipitous immersion experience in the high desert. The first week we occupied our house a balding white haired man (about our age now) drove an ancient four wheel drive Ford pickup straight from the road to our front door on what wasn’t intended to be a driveway. Ever so carefully, stiff of back, he exited his truck to greet the startled rookie homeowners. He announced himself: “Bill Collier, I’m your neighbor behind you”. He gestured vaguely to the northwest. His mission, he declared, was to meet us and bring us up to speed on the neighborhood and its history. We hadn’t asked but he started in on the telling. |

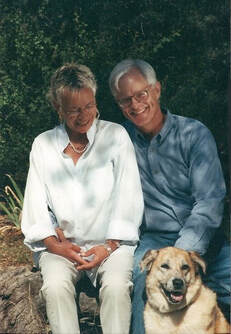

AuthorKaz and I moved to Oracle in 1979. The house we bought dated to the late 1940s. With little advance knowledge of the place, we set out to build a new life together, intending to settle in and raise a family. Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|