|

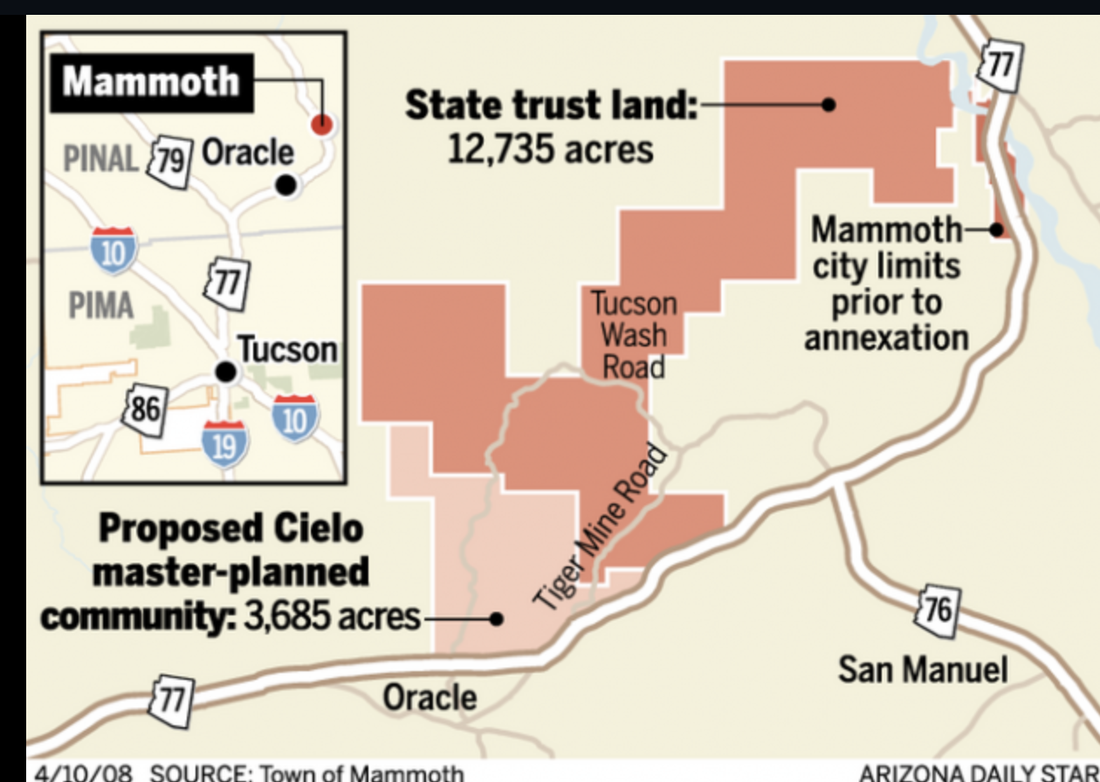

Tiny Mammoth has some big growth plans Fading community looking to revitalize through annexation of 16,490 acres By Brian J. Pedersen Arizona Daily Star Apr 10, 2008 A mammoth land grab by one of Arizona's smallest municipalities is being hailed by town officials as a way to finally bring growth and revitalization to a long-stagnant community. Critics, however, say the moves made by Mammoth late last year could spell doom by stretching thin an already-stretched revenue stream. In November, Mammoth, a former mining town 30 miles northeast of Oro Valley, annexed 16,490 acres that increased the size of the town from just under one square mile to almost 27. (To continue click the "read more" below) Most of the annexed territory is 12,735 acres of state trust land, which needed to be included in order for Mammoth to take in its target: a proposed master-planned community featuring more than 3,500 homes that Fairfield Homes hopes to develop on the north side of Arizona 77 near Oracle.

No timetable is set on when the homes would be built or what the size and price range would be. Mammoth's annexation occurred without much notice, though it has gained attention lately as Oro Valley moves forward with its own plans to annex 9,100 acres of state trust land known as Arroyo Grande north of town. Town's population is shrinking The 2000 U.S. Census lists Mammoth's population at 1,762, ranking it at the time as 79th among Arizona's 87 incorporated towns or cities. The town has been slowly losing residents over the years, as most of the towns in the upper San Pedro Valley have as nearby mines shut down. Incorporated in 1958, Mammoth has never been flush with cash, and its annual budget has actually declined due to a lack of revenue. The 2007-08 budget called for about $2.68 million in spending, down from $3.08 million for the 2006-07 fiscal year. A 2 percent town sales tax brought in only $70,045 last fiscal year, compared with nearly $800,000 in state-shared revenues that are in the cross hairs of the Legislature as it tries to shore up a $1 billion budget shortfall. Without much in the way of moneymaking operations within town limits, Mammoth officials say they jumped at the chance to take in Cielo, a 3,685-acre development where Fairfield hopes to eventually put 3,538 homes. "I think it can help us by bringing us on the scene," said Syble Ramirez, a Mammoth councilwoman who has lived in the town for 37 years. "This will get people interested in us. The only reason I wanted to do this was for the future of our children and our grandchildren." Cielo also will have plenty of commercial development, planners say, as well as a water-treatment plant and a wastewater-treatment facility that Fairfield intends to deed over to Mammoth. "Mammoth was a huge, thriving mining town, but now it's been dying on the vine," said Frank Thompson, a planner working with Fairfield on Cielo. "Now they will have funds to revitalize the existing town." 10 minutes from Mammoth Cielo is about nine miles southwest of Mammoth's southernmost boundary, roughly a 10-minute drive along Highway 77. Since state law does not allow municipalities to annex land that isn't adjacent to existing town boundaries, Mammoth needed to go after the land in between it and Cielo in order for the annexation to be legal. That meant taking in state trust land, which is owned by the Arizona State Land Department. That department sells off its land in chunks for the highest price available to benefit the trust that pumps millions of dollars annually into the state's public school system. Currently, that land is nothing more than rolling hills and leased ranches, as well as portions of the renowned Arizona Trail and a series of significant washes that branch off from the San Pedro River just east of Mammoth. "We're pretty much on the extreme of each other," Mammoth Mayor Craig Williams said of the distance between the town proper and Cielo. "What's in between is pretty much really rugged wilderness area." Though rugged, and seemingly hard to develop, nothing in the Aug. 15, 2007, pre-annexation development agreement between Mammoth and the State Land Department would prevent that land from eventually being sold off to developers looking to cram in as many housing units as possible. That is the main concern of Pima County Administrator Chuck Huckelberry, who cited Mammoth's state-land annexation in a letter he sent to Oro Valley Mayor Paul Loomis in January. Though it's not in his county, Huckelberry sees a correlation between what Mammoth did and what Oro Valley is trying to do because of the existence of the pre-annexation agreement. Huckelberry wrote that the Mammoth agreement is "clearly in favor of the State Land Department" in that it makes requirements of the town in regard to the land but not of the landowner, the State Land Department. "It favors the landowners 100 percent," Huckelberry said. "There's no assurances that the rugged land would be set aside for anything other than development." Mammoth's agreement with the state calls for the trust land to shift from Pinal County's General Rural zoning designation — which permits one house for every 1.25 acres — to "the nearest equivalent zoning district in the town of Mammoth." According to Mammoth's general plan, amended in September, the state trust land is listed as being planned for the town's new Cluster and Master Planned Development option for which Cielo has been rezoned. Development possibilities If the state land were to be developed, it is likely to happen closer to Cielo and then move toward old Mammoth. The State Land Department said in a November 2006 report on the Mammoth annexation proposal that, because of the presence of Cielo to the south, the trust land "may be developed in three broad phases." The first would be a 6,420-acre chunk immediately north of Cielo that could tie into Cielo's planned roads as well as its water and wastewater systems. That would further feed into the belief of some that, though Mammoth could be on the cusp of exploding in population, there would be a distinct separation between what has been known as Mammoth and what will be considered Mammoth in the future. With estimates of between 8,000 and 9,000 people living in the Cielo development alone, Mammoth would likely need to build satellite offices of all its municipal operations in that area. Police Chief Neal Mullard is already planning for it, saying he'll need at least two new officers, one new vehicle and a police station to cover the area. Mullard said that while his police force is responsible for all of Mammoth's new territory, the only part he needs to concern himself with for the time being is the San Manuel Quarry, which lies just east of Fairfield's land and is operated by Kalamazoo Materials. "If something gets stolen out there, I'm going to have to go out there and fill out a police report," Mullard said. "That brings in a liability." The Public Works Department has eight employees handling the town's streets and parks, its water and wastewater systems and the town cemetery. "Everything is going to change here quite a bit," Public Works Director Juan Ponce said. To pay for the added responsibilities, town officials say they'll need to institute impact fees and levy a construction sales tax in order to gain revenue from the new homes. Impact fees are meant to pay for the impact that new homes would have on town services. "We've talked about those things," Williams says, noting that no timetable has been set on creating them. Residents welcome prospect The prospect of a large number of new homes and neighbors doesn't seem to bother Mammoth residents, who see only benefits coming from such an influx of growth. "It seems like it's going to help the town grow," said Gerald Seevers, 78, a former mine worker in San Manuel who has lived in Mammoth more than 30 years. "I'm really looking forward to it," said Lupe Ponce, a resident of Mammoth since 1961. "Right now we have to go to Tucson to do all our shopping." Williams, who has been mayor since June 2004, said nearly everyone in town has to look elsewhere for work. He's hoping the growth can bring jobs to the community. "We're hoping people like me won't have to drive so far," he said. "Everyone either works at (the mine in) Hayden, or in Tucson, or like me they work in Florence for Pinal County." Some express reservations While those in town are eagerly awaiting Cielo — which planner Thompson says, depending on how the housing market goes, is probably at least a few years away from even breaking ground — there are some people close to the anticipated growth who aren't so happy about it. Residents of Oracle, an unincorporated community of about 5,000 just beyond Mammoth's new western boundary, worry that all those new homes will put a burden on them until Mammoth gets around to servicing that area. Longtime Oracle resident Bill Wood questions whether Mammoth will actually be able to afford to manage its new land. "I think that they're going to be in financial trouble," Wood said. "I think the trouble is yet to come, yet to be realized. The town is now responsible for the policing, the roads and any schooling. I think they're overambitious. Now they've done it to themselves." Mammoth, by the numbers 619 The town's size, in acres, as of Nov. 28, 2007. 0.96 The town's size, in square miles, as of Nov. 28, 2007. 16,490 Size, in acres, of land annexed on Nov. 29, 2007. 25.8 Size, in square miles, of land annexed on Nov. 29, 2007. 1,762 Population of Mammoth, according to the 2000 U.S. Census (it ranked 79th out of 87 municipalities in Arizona). 8,845 Estimated number of residents expected to live in Cielo, a proposed 3,538-home (yet to be built) master-planned community included in the annexation. ● Contact reporter Brian J. Pedersen at 434-4079 or [email protected].

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorKaz and I moved to Oracle in 1979. The house we bought dated to the late 1940s. With little advance knowledge of the place, we set out to build a new life together, intending to settle in and raise a family. Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|